According to numerous reports, crimes against humanity have been committed in Coahuila, including underlying acts of murder, torture, and forced disappearances.1The Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) report argues that the criminal group Zetas pursued a policy of controlling territory that led to widespread or systematic attacks on Mexico’s civilian population, constituting crimes against humanity. Open Society Foundations, Undeniable Atrocities: Confronting Crimes against Humanity in Mexico, 2016; “México: Asesinatos, desapariciones y torturas en Coahuila de Zaragoza constituyen crímenes de lesa humanidad: Comunicación a la Corte Penal Internacional,” Federación Internacional de Derechos Humanos, 2017, www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/rapport-mexique-num-5-3.pdf; Open Society Justice Initiative, Corruption that Kills: Why Mexico Needs an International Mechanism to Combat Impunity, New York, NY: Open Society Foundations, 2018, www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/corruption-that-kills-es-20180502.pdf. In recent years, Coahuila has been widely studied by academics, human rights organizations, and international organizations, within the wider context of insecurity and abuse in Mexico, for several reasons.2Sergio Aguayo and Jacobo Dayán, “El Yugo Zeta: Norte de Coahuila, 2010-2011,” Ciudad de México: El Colegio de México, Novemver 2017; “‘Control…Sobre Todo el Estado de Coahuila’: Un análisis de testimonios en juicios contra integrantes de Los Zetas en San Antonio, Austin y Del Rio, Texas,” Human Rights Clinic – The University of Texas School of Law, November 2017, https://law.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2017/11/2017-HRC-coahuilareport-ES.pdf. First, the state registered a significant surge in violence between 2009 and 2012. Second, trials in Texas against state public servants and against members of organized crime groups provided valuable information regarding high-level cases of embezzlement, corruption, and money laundering, on one hand, and into the Zetas’s violent operations, on the other. Finally, civil society groups and organized families of victims have become a national and international reference in their struggle to establish justice and truth-seeking measures.

While this project builds on other reports and studies that have focused on the participation and collusion of state officials in the commission of grave crimes in Coahuila, this is the first approximation that places at the center the economic and financial connections between public officials, companies, and criminal actors. As such, it proposes to examine the distribution and excercise of violence through the analysis of illicit flows and state capture in Coahuila, a form of corruption in which private interests collude with public actors to dominate policy-making for private gain in detriment to the public interest.3State capture refers to “efforts of firms to influence the contents of legislation, rules, laws, decrees or regulations (i.e. the basic rules of the game) through unofficial payments by private actors to public officials.” See: Joel S Hellman, Geraint Jones, and Daniel Kaufmann, “Seize the State, Seize the Day: An Empirical Analysis of State Capture and Corruption in Transition,” The World Bank, April 2000, 43.

The level of impunity that is experienced in Coahuila, and in Mexico in general, cannot be understood without analyzing the power structures in place and the inherently complex web of interactions between political, economic, and criminal actors.

In the context of insecurity, an intricate system of relationships and extralegal arrangements are put in place between actors that employ violence to sustain, or revert, power structures. Often, while economic and financial networks have a regional, national, and international dimension, criminal networks — those that require territorial control to operate — ultimately appear at the local level. Making the link between the financial and the criminal, identifying where they interact and overlap, is fundamental for truth-seeking measures. One depends upon the other.

The glass ceiling of impunity

In the struggle for justice for grave human rights violations in Mexico, victims often face a glass ceiling of impunity. Not only are there significant weaknesses in the Mexican judicial system and in local capacities to prosecute crimes, but the adjudication of responsibility is often limited to the direct perpetrators of violence and rarely links to the intellectual authors, facilitators, or profiteers of the crimes.

In this sense, Coahuila is not the exception. First, the same political party that governed Mexico for over 70 years, the PRI, has governed Coahuila since 1941. Key PRI politicians have jumped from one position to another within state and municipal governments over the last four administrations. Public servants, unsurprisingly, have been exonerated (or simply not investigated) by state institutions despite being found guilty in other jurisdictions (such as the U.S.) for economic crimes, such as embezzlement, misappropriation, and money laundering.

Jump to the Cargografías tool to trace the political careers of key individuals within the Coahuila state administration between 2005 and 2017

Starting in 2009, Humberto Moreira’s government passed significant institutional reforms to the state public administration, many promoted by the Coahuila Secretary of State (Secretaría de Gobierno). Between March and June 2009, the Coahuila state government transferred the duties of the Secretary of Public Security, the State Penitentiary System, and the Office of the General Prosecutor of the State of Coahuila to a new entity called the Office of the Attorney-General of the State of Coahuila (Fiscalía General del Estado de Coahuila, hereinafter Fiscalía). The lack of division of powers, however, reinforced impunity in the state and reduced institutional accountability by placing them all under the oversight of the Fiscalía, under Jesús Torres Charles, linked to organized crime in U.S. court testimonies.4“México: Asesinatos, Desapariciones y Torturas En Coahuila de Zaragoza Constituyen Crímenes de Lesa Humanidad: Comunicación a La Corte Penal Internacional,” Federación Internacional de Derechos Humanos, 2017, https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/rapport-mexique-num-5-3.pdf.

A second institutional reform in April 2010 created the Coahuila Tax Administration Service (Servicio de Administración Tributaria del Estado de Coahuila – SATEC), the government entity responsible for state revenue collection and administration. Between April and December 2010, the SATEC was given increased functions and budget oversight, including the contracting of debt and bond issues. Rents derived from the following independent government bodies were transferred to the SATEC: Promotora para el Desarrollo Minero (Prodemi), the Promotora Inmobiliaria para el Desarrollo Económico de Coahuila (Pideco), the Comisión Estatal de Agua y Saneamiento (CEAS), and the newly created state company Servicios Estatales Aeroportuarios (SEA). Between 2010 and 2011, Hector Javier Villarreal Hernandez presided the SATEC, period in which Coahuila’s debt increased from MXN 7.4 billion to MXN 35.5 billion. In 2014, Villarreal Hernandez pleaded guilty to federal money laundering charges in the U.S.

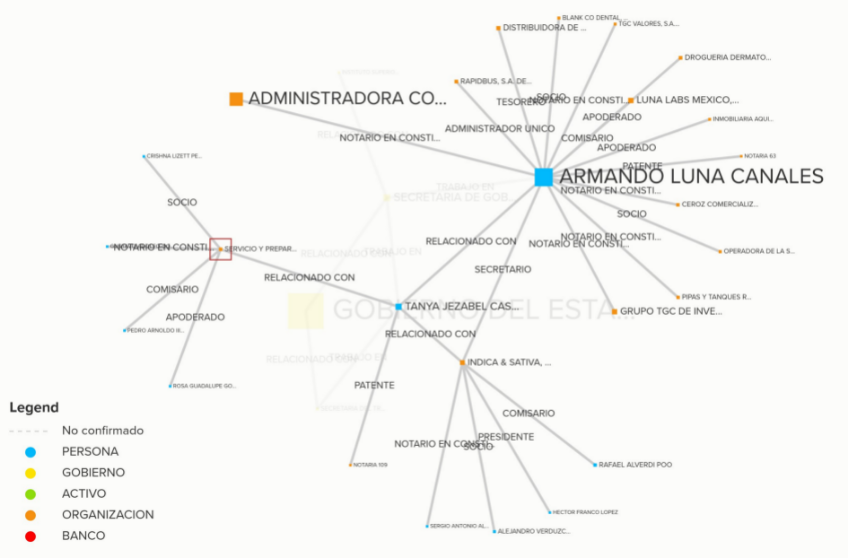

The role of the Secretary of State (Secretaría de Gobierno) in this institutional engineering was fundamental. During the period 2005-16, there was certain continuity in the leadership of the institution. Armando Luna Canales, originally from Saltillo, occupied the position on two occasions: the first with Humberto Moreira between 2008 and 2011, and the second with his brother Ruben Moreira between 2012 and 2015. Luna Canales’s professional trajectory has been primarily in government. Self-reported information in asset declarations, and searches in SIGER and MARCANET, indicate that he has also maintained significant interests in the private sector. Furthermore, in 2008 Luna Canales obtained a patent to act as a public notary in Coahuila. The following diagram maps his and his family’s commercial interests, as well as the companies that he has incorporated in his capacity as notary.

The case of Luna Canales raises the question regarding the role public notaries have in the incorporation of companies and in the transfer of property in Mexico. In both acts, the responsibility to verify and validate information and the identity of the parties falls entirely to the notary. In Coahuila, much like other states in the country, patents to act as notaries have been conceded, many times as a “gift,” to public servants once they leave their posts.

The mapping of key public servants’ commercial interests in Coahuila confirms that there is a false separation between political and economic power in the state. On the contrary, it would appear that one strengthens the other. Even though the commercial interests network focuses on the period 2005-17 — that is, on the administrations of the Moreira brothers —, the names of past Coahuila governors also appear in the network, including those of Rogelio Montemayor y Seguy (1993-99) and Enrique Martínez y Martínez (1999-2005).

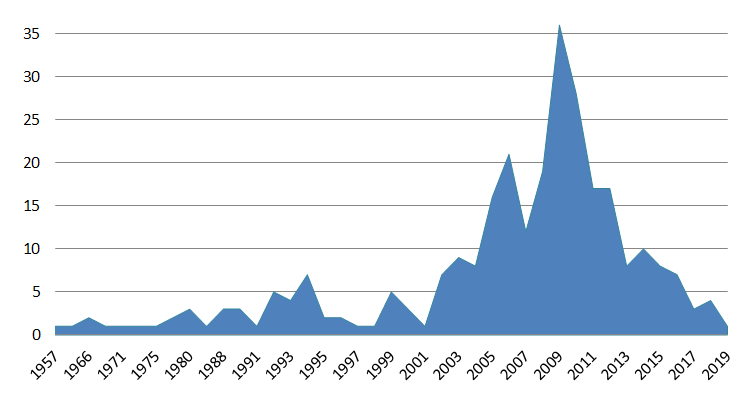

The following chart depicts the distribution of incorporation dates of the companies included in the commercial interests network. Since the analysis was centered on the period between 2005 and 2017, it is unsurprising that the year with the most incorporated companies was 2009 and that, between 2009 and 2010, almost 23% of all analyzed companies were incorporated. What is significant about this is that: i) public servants and their immediate network start incorporating entities as they gained political power; ii) the period between 2009 and 2011 coincides with one of the largest cases of misappropriation of public funds in the history of Coahuila; and iii) the period coincides with the surge in violence in the state, though this did not inhibit the commercial activities of the ruling class. It is evident that companies are often used to obscure the capture and transfer of financial flows; their role within the wider macro-criminal networks, therefore, must be examined and understood.

Graph. Year of incorporation of analyzed companies

Debt and misappropriation

As previously stated, in 2010 the SATEC began concentrating functions of revenue collection and contracting debt using the state’s federal allocation of funds as its guarantee. The SATEC, however, became highly controversial for its role in the state’s massive debt and for the participation of several of its officials in fraudulent schemes for the appropriation and diversion of public resources. This network centered around Héctor Javier Villarreal Hernández and Jorge Juan Torres López — both facing trials in the U.S. for embezzlement of public funds and money laundering —, but also involved key officials within the Coahuila Secretary of Finance, the State Water and Sanitation Commission (CEAS), and the Secretary of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP) of the Federal Government. The SATEC disappeared in the first months of the Rubén Moreira government.

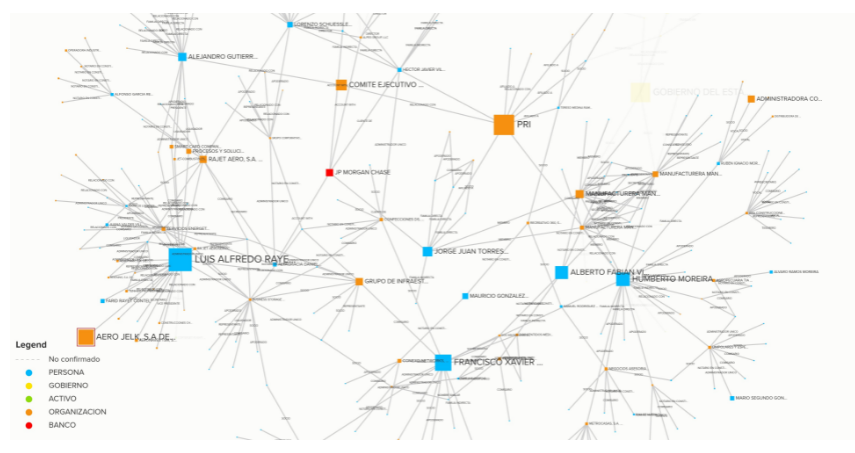

Between 2008 and 2011, the Federal Auditor’s Office (Auditoría Superior de la Federación – ASF) identified that the debt in Coahuila had passed from MXN 1,800 million to MXN 35,541 million, an increase of 1,874%. The embezzlement of public funds was facilitated by various actors, including notaries, intermediaries, and banks. Héctor Villarreal and Jorge Torres involved family members and close associates in the network of companies and bank accounts used to move money across borders, as seen in the following diagram.

The issue of Coahuila’s debt is not the only example of a massive transfer of public funds to the private sector. If we analyze the scheme of corruption and money laundering involving businessmen Luis Alfredo Rayet Díaz, Luis Carlos Castillo Cervantes, and Alejandro Gutiérrez Gutiérrez — all facing trials for financial crimes either in Mexico or in the U.S. —, we see how business interest networks begin to overlap. For instance, Lorenzo Schuessler Jr., the brother-in-law of Javier Villarreal and linked to his legal process in the U.S., participated as legal representative of the company Rajet Aereo, S.A. de C.V., controlled by the Rayet family. At the same time, Luis Alfredo Rayet Díaz and Alejandro Gutiérrez Gutiérrez are linked through three companies since at least 2003. In the company Jet-Combustibles, S.A. de C.V., Alejandro was listed as partner and Luis Alfredo as sole administrator.

In 2007, both incorporated the company Smart Card Company de México, S.A. de C.V., in Ramos Arizpe, a service company operating in the aeronautical sector.

It is important to note that, at this level of analysis, we are not providing an opinion of the individual responsibility of these individuals and/or companies in specific crimes, but rather mapping out economic networks around actors formally accused of committing financial crimes in Mexico or abroad, such as the cases of Héctor Javier Villarreal Hernández and Jorge Juan Torres López (Criminal Proceeding C-13-1075) and that of Luis Carlos Castillo Cervantes (C-16-cr-00802).

Financial operators of armed criminal groups

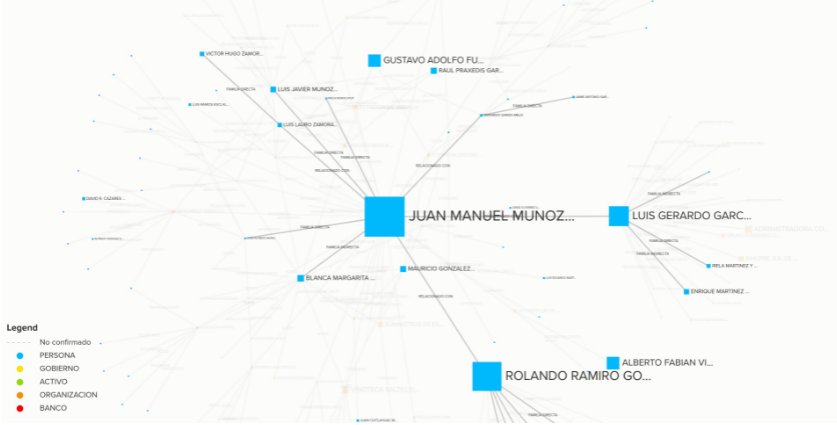

Corporate vehicles are used and abused to obscure illicit flows within the national and global financial systems. In March 2016, Juan Manuel Muñoz Luevano was arrested in Spain to be extradited to the U.S. three years later. Muñoz had been identified as the financial operator of several organized crime groups operating in Coahuila, primarily the Zetas. In May 2019, he pleaded guilty before a District Judge in San Antonio, Texas, for charges of conspiracy of money laundering.

Since his arrest, several public servants have been liked to his network of companies and associations. The following network graph shows these links, as confirmed through SIGER:

The network’s reach is considerable. An analysis of Muñoz’s commercial interests, furthermore, highlights the participation of key individuals within his network of gasoline companies in Coahuila, such as the case of Gustavo Adolfo Fuentes Yañez and Victor Manuel Rodríguez Sáenz. Again, it is important to note the role of notaries within macro-criminal networks and within Muñoz’s network specifically. Many of the companies incorporated by Muñoz and his closer network rely on the same individuals to notarize the incorporation of companies, the changes in ownership structure, and even the transfer of properties. Illicit financial flows are facilitated through these structures.

What’s next?

Download the full report on Veracruz, or explore the Coahuila network graph. If you identify new relationships, share them with us at info@empowerllc.net . All information in the database and DocumentCloud is for public use; we just ask that you give us credit.

Click here to download our follow-the-money and open-source research guide.